Concert Photography: Part 1—The Vanishing Value of Photography

By Scott W. Coleman

Concert photography used to pay the rent. Today, it barely pays for parking.

Once, a single shot from the pit could land on a magazine cover, might be reused for tour previews, or live on in a band’s press kit. Those images were assets—invaluable to the photographer, the publication and the artist. They provided not just a paycheck, but a record of culture.

Now, most of those revenue streams are dead. Rights-grab contracts don’t just block resale—they sometimes forbid use beyond a few days after the show. That’s a death sentence for archival usage.

Imagine a publication that pays to send a photographer. When the same band returns six months later, editors might reuse those same images for a preview—an inexpensive and effective way to generate coverage. That would benefit the band, the promoter, and the audience. But restrictive releases often prohibit it, killing a useful opportunity that once sustained photographers and news outlets alike.

Tom Petty’s team offered a rare counterexample. His photo releases outlined clear, reasonable compensation if his team selected an image for album artwork or tour promotion. In other words: if you wanted the photo for commercial use, you paid the photographer. Petty’s camp recognized the value of images, showed respect and cleared terms in advance. That kind of model was professional, transparent and fair.

Contrast that with Taylor Swift.

The Swift Case: One-Time Use and Nothing More

Swift’s tour photo contracts drew sharp criticism in 2015 when they limited photographers to “one-time only” use of images, while granting the artist’s team broad rights to reuse those same images in perpetuity, without additional pay. Photographers were prohibited from using the images for portfolios, self-promotion or resale.

One editorial photographer put it bluntly: “A complete rights grab, and demands that you are granted free and unlimited use of our work, worldwide, for all eternity.”

Some outlets refused to play along. The Irish Times declined to run any photos rather than accept Swift’s restrictive terms. Other editors were forced to fall back on handouts, which amount to promotional materials—not journalism.

Swift’s camp defended the clauses, arguing that copyright was not transferred and that future usage could be approved case by case. But the damage was done. A photo that might have carried value for months—or years—was locked down to a single day’s coverage.

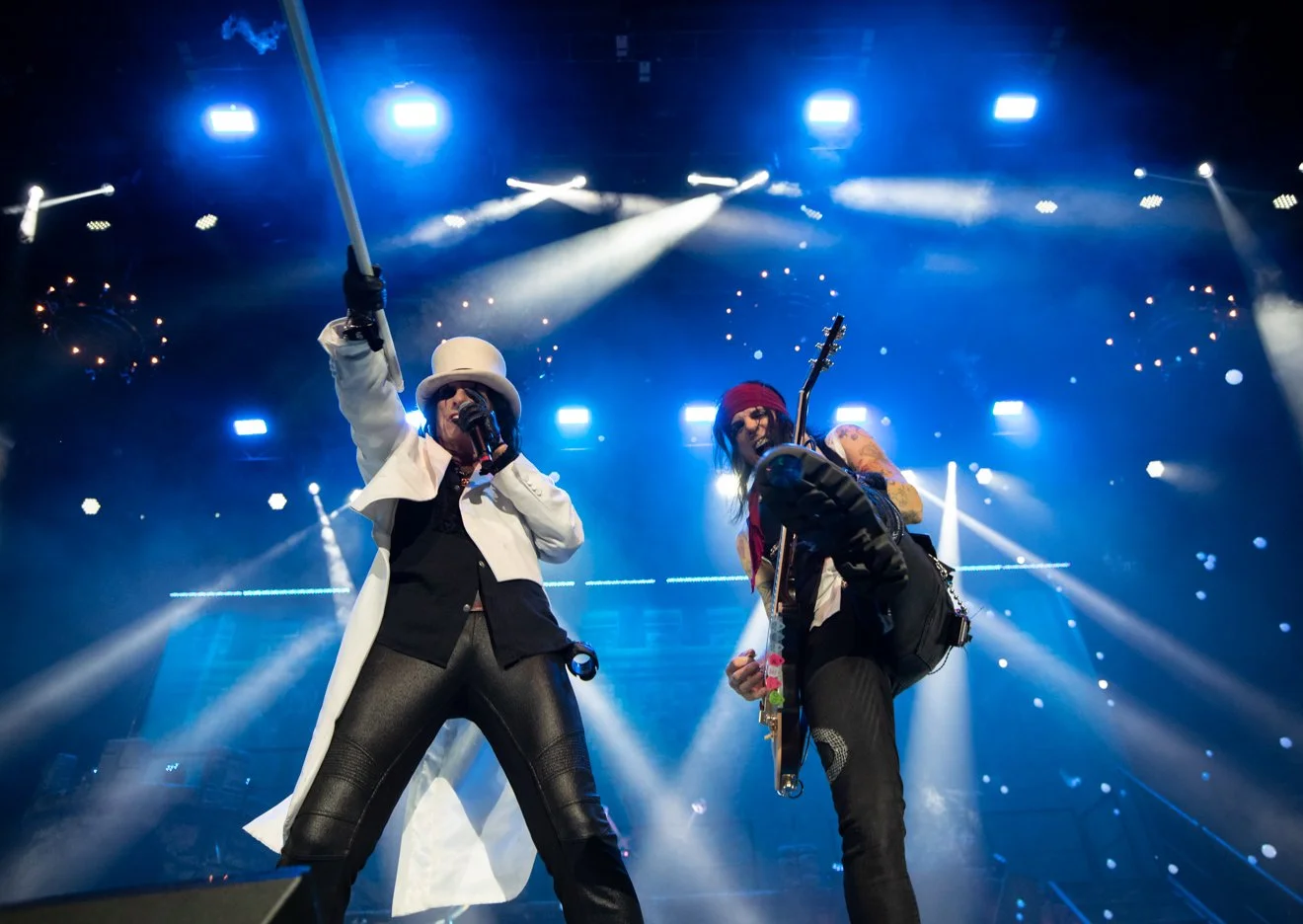

Foo Fighters, Guns N’ Roses, 311: More of the Same

Swift wasn’t an outlier. Foo Fighters and Guns N’ Roses have both issued contracts that limit resale or demand rights transfers as a condition of access. Photographers covering 311’s “311 Day” events—marquee shows that generate global fan buzz—report similar limitations, despite the clear publicity value of professional images.

These practices leave photographers with little leverage. Accept the deal, and your work is stripped of future value. Refuse, and someone else will take your spot in the pit for free.

The system is designed to reinforce itself. And the parallels with what’s happened to musicians are obvious.

Musicians in the Same Trap

For decades, musicians made a living from album sales, publishing rights and touring. The digital shift blew that apart. Spotify and Apple Music pay fractions of a cent per stream. Most charting artists can’t even come close to surviving on streaming revenue.

Meanwhile, Live Nation and Ticketmaster—the world’s dominant concert promoter and ticketing company—have consolidated control of venues, tours and ticket sales. For working bands, the result is an economic squeeze that looks awfully familiar to anyone holding a camera.

Live Nation: The Market-Maker

Live Nation merged with Ticketmaster in 2010. The Justice Department approved the deal under a consent decree, meant to limit anticompetitive behavior. Less than a decade later, the DOJ accused Live Nation of violating that decree. It was extended in 2019 and now runs through 2025. And in 2024, DOJ and 30 state attorneys general sued to break the company up, calling Live Nation a monopoly that harms fans, artists and venues alike.¹

Live Nation’s own filings show the scale. As of its most recent 10-K, the company owns, operates or has exclusive booking rights to nearly 400 venues worldwide. DOJ’s complaint put the North American figure at more than 265, including over 60 of the top 100 U.S. amphitheaters.²

That vertical stack—promotion, venues, ticketing—lets one company set the tone for entire markets. DOJ’s complaint said it plainly:

““We allege that Live Nation relies on unlawful, anticompetitive conduct… The result is that fans pay more in fees, artists have fewer opportunities to play concerts, smaller promoters get squeezed out, and venues have fewer real choices for ticketing services.”³”

Live Nation disputes the allegations. The company says the DOJ’s case misunderstands the economics of live music and won’t reduce prices for fans. Their message: integration creates efficiencies. DOJ’s message: it creates a chokehold. The courts will decide.

Austin as a Case Study

In 2014, Live Nation purchased a controlling stake in Austin-based C3 Presents, the promoter behind Austin City Limits Festival and Lollapalooza. At the time, reports put the stake at 51 percent.⁴

Even before the ink was dry, Austin venues felt the impact. In 2010, the Austin Chronicle reported that C3’s exclusivity agreements effectively blocked about 130 bands from playing independent venues for nine months out of the year. The radius extended hundreds of miles, mirroring clauses used at Lollapalooza in Chicago—300 miles, 180 days before and 90 days after the festival.⁵

If you’re running a 600-cap club, that’s not paperwork. That’s empty nights on the calendar. For staff, it’s lost shifts. For small promoters, it’s higher risk and thinner margins.

The bigger the radius and the longer the blackout, the fewer options independent venues have. And the more leverage Live Nation has to dictate terms—not just to musicians, but to photographers whose access is controlled by the same promoters.

Rights Grabs as Part of the Same Machine

When one company owns the venues, books the tours and sells the tickets, it also controls the pit. That leverage makes restrictive photo releases easier to enforce.

If a promoter controls the show calendar in your city, you’re less likely to risk saying no to a rights-grab contract. Walk away, and you might not just lose one gig—you might lose an entire market.

That’s not a sustainable system for artists, for photographers, or for the crews and staff who rely on steady shows. It’s a system designed to maximize profit at the top, while cutting off income streams at the bottom.

Why This Matters

When a profession loses its value, it loses its voice. If photography becomes free promotion instead of journalism, we lose independent documentation of culture. A cracked stage. A fan fainting. A crowd breaking through a gate. Or a mass shooting. Those should not depend on PR images from an artist’s team that will probably never come—they’re real, live history that deserves documentation.

Music photography is journalism. It carries truth, nuance and authenticity—all things that rights-grab contracts and corporate consolidation try to squeeze out.

And like journalism itself, it’s worth fighting for.

Real-World Takeaways

Musicians and photographers share the same struggle. Both are being squeezed by contracts and corporations that prioritize profit over art.

Publications must demand fair terms. Without them, coverage becomes PR, not journalism.

Fans have a role. Support independent venues. Pay for music. Recognize that if it’s free to you, someone else is paying the price.

Advocacy is essential. Norway’s photographers proved collective resistance can work. Musicians and photographers in the U.S. need the same backbone.

Footnotes

U.S. Department of Justice, “Justice Department Sues Live Nation-Ticketmaster for Monopolization,” May 23, 2024.Live Nation Entertainment, Inc., Form 10-K (2023); DOJ Complaint, 2024.DOJ Complaint, 2024.Billboard, “Live Nation Acquires Controlling Stake in C3 Presents,” Dec. 22, 2014.Austin Chronicle, “Radius Clauses Draw Scrutiny,” Aug. 6, 2010.